Currently, Johnsongrass is the only grass listed on the Missouri Department of Agriculture’s noxious weeds list. This perennial grass can reach over 6 feet in height, is found throughout the U.S., from Massachusetts to Florida to southern California, and can live in habitats ranging from roadside ditches to pastures to agronomic crop fields (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Johnsongrass growing in the perimeter of a soybean field.

Identifying Johnsongrass

Johnsongrass produces rhizomes, which are root-like structures that spread underground and are the vegetative structures from which new shoots emerge (Figure 2). Johnsongrass also forms large seed heads. These seed heads, or panicles, have a purple tint, and the seeds are approximately 3 millimeters to 5 millimeters in length (just under 1/8th of an inch). One plant can produce as many as 80,000 seeds in one year.

The leaves of Johnsongrass are hairless (or glabrous), reach about 6 to 20 inches in length, and have white midveins as they reach maturity (Figure 3).

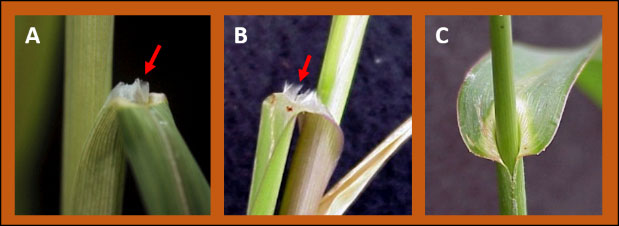

Prior to the formation of a seed head, this grass can be mistaken for barnyardgrass and/or fall panicum as all three grasses have leaves with prominent midveins. However, the ligules, or thin structures that occur at the junction between the leaf and stem, are membranous on Johnsongrass, consist of a fringe of hairs on fall panicum, and are altogether absent on barnyardgrass (Figure 4). Additionally, both barnyardgrass and fall panicum lack rhizomes.

Figure 2: A Johnsongrass rhizome: these structures spread underground and produce new shoots.

Another weed that is easily confused with Johnsongrass is shattercane (Sorghum bicolor). Shattercane is a member of the same genus as Johnsongrass, looks very similar to Johnsongrass throughout its lifecycle, but is an annual plant and lacks rhizomes.

The origins of Johnsongrass introduction in the U.S. are debated, however, the consensus is that the seed was introduced as a forage crop in the 19th century. The end of the Civil War may have aided in the weeds rapid movement across the country as authorities ordered that the grass be planted in eroded soils that had been fallow during the war. Regardless of when Johnsongrass actually spread, the control and eradication of this weed has been challenging ever since.

Figure 3: A mature Johnsongrass leaf has a prominent, white, midvein.

Control Program

At a minimum, Johnsongrass control programs should seek to: 1) prevent spread of rhizomes from infested to un-infested areas 2) kill or weaken established plants and their underground rhizome root system 3) control seedlings that originate from shattered seed, and 4) prevent production of seed and its spread to new areas.

It is also important to note that glyphosate-resistant (group 9) biotypes of Johnsongrass have been reported in nine U.S. states, and also that Johnsongrass populations with resistance to Group 2 ACCase-inhibiting herbicides (SelectMax, Assure II, Fusilade, etc.) occur in at least five states.

Fall is actually a very effective time for controlling Johnsongrass with herbicides, as the net flow of carbohydrates and photosynthates within the plant is towards the rootstocks. Therefore, by applying a herbicide at this time of year, more herbicide is translocated into the roots, resulting in better long-term control of this troublesome perennial weed species.

One of the most effective herbicide treatments for this weed is glyphosate. If the plants have been cut off with a sickle mower or combine, make sure to wait for the plants to resume active growth before treatment. Field infestations of Johnsongrass should also be minimized by actively controlling the Johnsongrass in the non-planted areas surrounding the field and by driving field equipment around weedy patches instead of through them.

Figure 4: The ligules on Johnsongrass leaves (A) are membranous, while the ligules on Fall Panicum leaves (B) are a fringe of hairs. Barnyardgrass (C) lacks ligules.

For more information on this intriguing weed and others, visit www.weedid.missouri.edu. For information on the identification of grass weeds that are common in Missouri, purchase or download a copy of IPM1024, Identifying Grass Seedlings at http://weedscience.missouri.edu/publications/ipm1024.pdf.

For more information on Missouri’s noxious weed list, control measures, and laws, please visit the Missouri Department of Agriculture Web site at agriculture.mo.gov/plants/ipm/noxiousweeds.php.