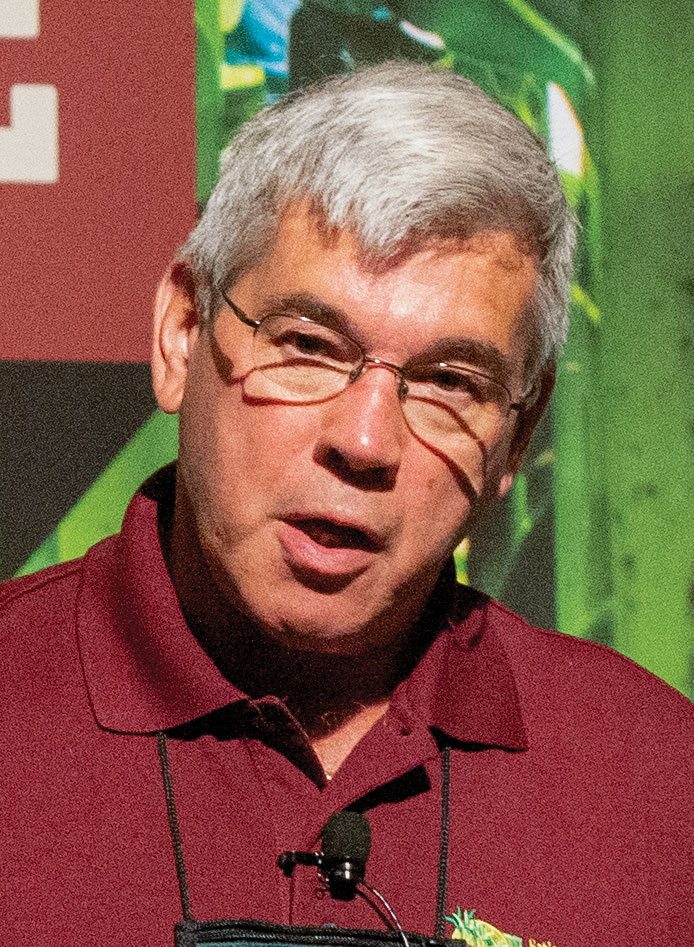

Pictured Above: CHANGE FOR THE BETTER. Starting as a conventional farmer, Iowan Wayne Fredericks began reducing tillage on his 750-acre farm in the early 1990s when he switched to no-till soybeans. Later, he switched to strip-tilled corn and introduced cover crops. The changes have brought him considerable fertilizer savings, water use efficiency and organic matter increases.

In principal, the benefits of reducing tillage and introducing cover crops seems intuitive. But, for farmers like Osage, Iowa, strip-tiller Wayne Fredericks, it’s important to textualize these benefits with research, data and his checkbook.

Like most farmers, Fredericks has collected data and made operational changes throughout the course of their farming career on he and his wife, Ruth’s, 750-acre operation. But unlike most farmers, he’s committed himself to being a wide-open book for study.

Working with Jerry Hatfield, retired USDA plant physiologist, the duo has collected data on Fredericks’s soil health to build a comprehensive understanding of the impact of increasing soil health through reduced tillage and cover crops.

Between moving to strip-tilled corn in 2001 and incorporating cover crops in 2012, Fredericks has seen a 30% reduction in both nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) application and a 2.5% increase in organic matter over time. Mostly, he credits cover crops, along with his commercial corn crop, as a successful combination in sequestering carbon.

Making a detailed of analysis of the changes in organic matter, crop yield, spatial variation in the fields and water and nutrient efficiency, the farmer and scientist team strives to leave out the guesswork and assign hard values to operational changes.

Transition Toward Reduced Tillage

Describing himself as a “fully conventional farmer” at the beginning of his farming career, Fredericks says the first big change he made on his farm was in 1991 when he started no-tilling soybeans.

“For those first 19 years, we would plow everything — plowing all our corn stalks and working bean stubble ahead of corn planting,” Fredericks says. “In the winter of 1991, we actually froze up early and couldn’t get any plowing done.”

“Enhanced water availability really does have a dollar value — we believe in an 80/20 rule. We lose 20% of our yield 80% of the time because we do not have enough plant available moisture at the right time…” – Wayne Fredericks

Not quite sure what to do, Fredericks remembered reading about a farmer who’d used a John Deere 750 drill to no-till soybeans. Despite it not being a popular practice at the time, he took the chance.

Right away, he noticed weed control benefits, but it wasn’t until harvest time that he was completely sold on the change.

“Our soybeans grew well, we got a great stand,” he says. “But most importantly, it yielded excellent. From that point on, there was no going back to the plow for me.”

The next big change on the farm came about a decade later when he switched to strip-tilling his corn. Providing an opportunity to try it, Fredericks’s fertilizer dealer was the one to buy a strip-till rig. However, after letting him work some of his corn acreage, Fredericks quickly saw the benefits for himself.

“I had greater fertilizer efficiency in the seedbed, warmed up the soil sooner in the spring, and there’s the reduced labor and implement costs among other huge savings,” he says. “But what we’re really after is getting a uniform, beautiful stand of corn established in those strips and still having that protective residue on the soil.”

The last big practice change on Fredericks’s farm didn’t come till later in 2012 when he started experimenting with cover crops. Chasing moisture, nutrient and N retention on his fields, he began various trials.

“We needed to find out what worked in our part of the state when it came to seeding rates, species, planting methods, termination methods and how herbicides affected yield and so forth,” says Fredericks.

After several years of experimentation and varying degrees of success, Fredericks began crossing paths with Hatfield at soil health meetings. It was then that the two joined forces to try to build a more scientific understanding on exactly what sort of benefits Fredericks was experiencing on his farm from his changing practices.

Fertilizer Savings

While maintaining rough parity with county average corn yields, often beating them by about 5 bushels-per-acre, Fredericks and Hatfield wanted to examine the cost savings specifically on fertilizer; given his practices. Using the Iowa State University (ISU) fertilizer crop budget recommendations for 2003 through 2018, they compared on-farm expenses from the same time period.

SAVING ON INPUTS. While maintaining rough parity with county average corn yields, often beating them by about 5 bushels-per-acre, Wayne Fredericks saw a considerable fertilizer savings as a product of his changing fertilization practices.

“We’re pretty much following Iowa’s crop budget nitrogen recommendations — 140-150 pounds per acre in a corn and soybean rotation,” Fredericks says. “Compared to a lot of producers running considerably more, there’s already a cost savings there. But, when it came to the P and potassium (K) budget, we were averaging $8.75 per acre less than ISU crop budgets across those years. We’re a smaller operation, but that adds up quickly. All while not compromising yields.”

Organic Matter Increase

A change Fredericks had noted himself early on was the slow climb of his organic matter content in the fields where he’d stopped conventional tillage.

“Back in the early 1980s, my crop consultant felt the need to pull organic matter samples so we knew what herbicide rates to use,” he says. “At the time, our fields varied from 2.3-3.3%, which is pretty common for my area. However, after we’d been no-tilling and strip-tilling for a while, we tested again in 2007. Then tested again in 2012 and 2015.”

Fredericks noted that over the course of 25 years, he’d seen a 2.5% increase in organic matter across the field.

BETTER PROTECTED SOIL. With a 2.5% increase in organic matter over 25 years, Wayne Fredericks believes his ability to store water has risen. By adding cover crops and reduced tillage, he’s seen greater infiltration during rainfall events. With more residue left on the surface of the field, there is also a decrease in evaporation.

“This is roughly one tenth of one percent per year,” he added. “Which, after talking with the University of Minnesota, I understand is a fairly doable increase in our latitude and part of the world to achieve simply by discontinuing full width tillage.”

Happy with the results, Fredericks wanted to know exactly how those increases affected his efficiency.

“This really doesn’t even mean much unless we value organic matter,” he says.

Taking a page from an NRCS (Natural Resources Conservation Service) study, Fredericks estimates that the incremental value of a one percent increase in organic matter is about $18 per acre in the form of enhanced water availability and $11 per acre in mineralization of N and P.

“Enhanced water availability really does have a dollar value — we believe in an 80/20 rule attributed to Dr. Hatfield that says: we lose 20% of our yield 80% of the time because we do not have enough plant available moisture at the right time,” says Fredericks.

Calculating the gains from his own organic matter increase, Fredericks believes he’s seen a $72 increase in value per acre.

“With the $18 in water availability and $11 in mineralization, we come up with a total of $29,” he says. “Being the simple farmer/mathematician I am, I just multiply the organic matter change that we’ve accumulated by that. So, with a 2.5% increase over time, that should bring you to a little over $72 in value on an annual basis that my farm ought to be worth more than the neighbors today.

“Capitalize that at 5% and we’re looking at my farm being worth $1,400 more per acre than the neighbors right over the fence because of the different methods we’re using.”

Water Use Efficiency

Placing a lot of emphasis on the importance of plant available moisture, Hatfield looked closely at how the methods Fredericks was using affected his crops over time.

“Obviously because of the increasing organic matter, there is the capability of storing more water,” he says. “With adding cover crops and reduced tillage, we have greater infiltration during rainfall events. With residues on the surface, there is a decrease in evaporation. So all this brings in more resilience in years with uneven distribution of rainfall.”

“In 2004, fields yielded 3.9 bushels per inch of rainfall. Looking at 2018, that rose to 5.5 bushels per inch — that’s a 41% increase in water use efficiency over that time period…” – Jerry Hatfield

Hatfield says the data pulled from Fredericks’ field suggests that partially through water use efficiency, he’s converted some of his traditionally poorer soils into better producers — thus giving him more uniform and consistent yields farm wide.

This was especially obvious to Hatfield when he looked at historical rainfall totals against county average yields and compared them to Fredericks’ data. Charting that, it was clear at the county level, yield was negatively correlated with April and May rainfall while it was positively correlated with July and September rainfall.

“It’s during that time that you can see the impacts of improving the soil,” says Hatfield. “Looking at Wayne’s data, in 2004 he yielded 3.9 bushels per inch of rainfall. Looking at 2018, that rose to 5.5 bushels per inch — that’s a 41% increase in water use efficiency over that time period.

“Looking at a different field and time period; in 2005 he got 5.3 bushels per inch and in 2017 that increased to 7.9 bushels per inch — a 50% increase in efficiency. We’re making more efficient use of every bit of water that falls onto this crop because we have access to that water. The overall profitability of his fields has increased because the yields are more uniform.”

Interestingly, in the process this appears to have made Fredericks’s farm an exception to the seasonal rainfall yield correlations

Hatfield discovered.

“The fascinating part of this data is that, over time, the relationships between excessive spring rainfall and deficit summer rainfall have begun to diminish in Wayne’s fields,” says Hatfield. “Because he’s improved the soil structure and water dynamics, he’s no longer sensitive to the types of conditions that seem to impact the rest of the County.”