For two decades, Tony Vyn has been encouraging corn growers to adopt a “no plant left behind” mentality.

“The whole purpose was to really emphasize that if we want to get higher yields, we want every one of those plants able to compete equally with each other and produce a uniform-sized ear,” says the Purdue University agronomist.

Plant uniformity is often associated with plant spacing and uniform emergence. While Vyn says those play an important role, he contends that we’ve been forgetting about the uniformity of nutrients and water in the soil, and the root environment corn plants need to achieve uniformity.

Vyn says nutrient timing and placement are key influencers in this. While strip-tillers may be tempted to strictly band nutrients in the strips, Vyn says it’s important to apply the right rate at the right time and in the right place.

Avoid High N Banding

When it comes to the timing and placement of nitrogen (N), Vyn wants strip-tillers to reconsider banding high rates in their strips. That’s because their corn could experience temporary toxicity.

Research from Kansas State University looked at strip-tilled corn growth at V6 when different application methods were used. In the study, researchers tested three methods:

- All N, phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) applied as a starter in a 2-by-2-inch placement at planting.

- Half of NPK applied in a spring strip, and the remaining 50% in the 2-by-2 starter.

- All of the NPK banded in the strip in the spring. The N that was applied in the strip was urea banded 4-6 inches deep at rates of 80-160 pounds.

After 3 site-years of data, researchers found that when all nutrients were banded, corn growth at V6 was suppressed compared to the other two application methods. As urea rates increased, corn growth was even lower.

Vyn points out this wasn’t due to banding too close to planting, as there were at least 2 weeks between application and planting. But he suspects the harm may have been due to a lack of moisture.

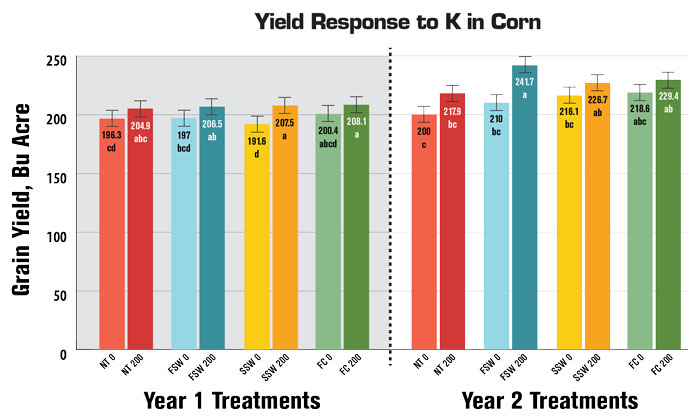

LONG-TERM IMPACTS FROM K. Researchers at Purdue University looked at how the potassium (K) product Aspire impacted corn yields under different tillage systems. In each system — no-till (NT), fall strip-till (FSW), spring strip-till (SSW) and fall chisel-plowed (FC) — they compared an application of 200 pounds of Aspire to no application. In the first year (L), the differences were pretty consistent, with the Aspire contributing 8-16 bushels. In the second corn crop (R), there was a big jump in yield response to the second application of Aspire where Aspire had also been applied in the fall strip-till system 2 years prior.

“That would be the kind of situation that would happen if you had dry soil conditions after the urea application,” he says. “A big window of time after a urea deep banding isn’t going to help you that much if the soils stay dry during that time.”

The corn eventually responded to the N in the urea and picked up a small yield benefit, performing about the same as the 50/50 application for an average 160 bushels per acre. But Vyn would prefer to see growers split-applying their N rather than banding it all at once.

“I’m much more in favor of using strip-till to apply 100-125 pounds of N than I am using strip-till to apply 200 pounds of N in one application,” he says, adding that strip-tillers should consider a coulter application or Y-Drops to apply remaining N later in the season.

Strip-tillers should also think about where they’re placing their nutrients in the strip. If it’s in the same place every year, that’s going to affect the soil pH over time.

“If you’ve got a fixed position for strip-till — you set your RTK up, you always follow the same pattern, and you always band UAN at a 200-pound rate right in the row — watch out when it comes to pH,” Vyn says.

He advises strip-tillers to consider repositioning their strips from year to year.

Meet Early N Needs

Strip-tillers also need to consider the rate of their N even if they’re not banding it in the strips.

Vyn shared a study where they compared two split N applications in strip-tilled corn. The corn was planted 7 inches apart within the row at a population of 29,000.

Can You Cut K Rates When Banding?

Some strip-tillers have wondered whether they can get away with lower rates of potassium (K) because they’re banding it. To answer that question, Purdue University agronomist Tony Vyn looked at a 100-pound rate of the K product Aspire in strip-tilled corn compared to both no K and a 200-pound rate. He tested these rates in both fall and spring strip-tilling.

In the first corn crop after these applications, the 200-pound rate resulted in a yield increase of about 4 bushels compared to the 100-pound rate in the fall strip-till, while the spring strip-tilled corn saw only a 2-bushel difference. But in the second corn crop 2 years later, which followed after a season of no-tilled soybeans without any added K, it jumped to about 10 bushels for the fall strip-till, while the spring strip-till was about 4 bushels higher over the 100-pound rate.

Vyn concluded that cutting K rates does not pay in the long-term and stressed that higher K levels in the ear leaf at R1 stage are essential to achieving higher corn yields.

On one plot, the N was split 50/50: 90 pounds at planting in a 4-by-2-inch placement and then 90 pounds sidedressed. The other plot had only 30 pounds applied at planting in the 4-by-2-inch band, and then 150 pounds were sidedressed.

Despite both plots receiving a total of 180 pounds of N, the differences in yield were drastic. Where the application was split into 30 and 150 pounds, the corn yielded an average of 169 bushels per acre. On the plot where 90 pounds was applied both times, the corn yielded an average 223 bushels per acre — 54 bushels higher. Visual comparison of the corn ears also confirmed the higher-yielding plots had more ear uniformity.

Don’t Skip Starter

One of the questions Vyn is most commonly asked by strip-tillers is whether they can have confidence in banding their P and K so that they can skip using a starter fertilizer at planting.

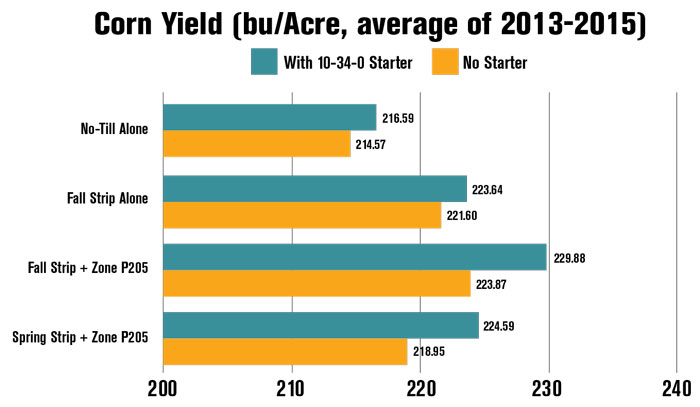

To test this, Vyn conducted research on fall and spring strip-tilling. He looked at both banding and not banding phosphate in fall strip-tilled corn, as well as applying vs. not applying a starter fertilizer. He kept banded phosphate in both spring strip-tilled plots but looked at whether there was an advantage to adding a starter fertilizer on top of that. The fertilizer banded was 150 pounds of Micro-Essentials-SZ (MESZ, a fertilizer that includes P, sulfur and zinc), which provides 60 pounds of phosphate, and the starter fertilizer was 10-34-0 applied in a 2-by-2-inch placement.

“I’m much more in favor of using strip-till to apply 100-125 pounds of nitrogen than I am using strip-till to apply 200 pounds of nitrogen in one application…”

Strip-tilling in the fall without phosphate banded or starter fertilizer applied yielded an average 221.6 bushels per acre, while the addition of the starter brought it up to 223.6. Banding phosphate in the fall strips without starter yielded an average 223.9 bushels per acre, and adding starter increased it by another 6 bushels to 229.9. Just banding phosphate in spring strips had the lowest average yield of 219, but adding starter brought it up to 224.6 bushels.

The results confirmed that strip-tillers shouldn’t rely on banding alone.

“That was kind of a wakeup call that there are going to be situations where you still need something, whether it’s in-furrow or 2-by-2, to give you an additional benefit,” Vyn says.

If you’re trying to achieve 250-300-bushel yields, you need to think about optimizing nutrient access, he adds. Only 45% of P is in the corn plant at flowering time, with most P going into the kernels, so growers need to think about both early vegetative growth and reproductive growth when it comes to P.

Fall Band K

K uptake in corn is very different from P — 90% of it is in corn by flowering time and is taken up very quickly in the vegetative stage.

So does it make sense to apply K in the fall or spring?

STARTER MAKES A DIFFERENCE. Purdue University looked at how much of a difference both banding phosphorus (P) and using a starter fertilizer made in corn yields under no-till, fall strip-till and spring strip-till. Banding P in fall strips along with a 10-34-0 starter had the highest yield of nearly 230 bushels per acre, followed by banding P in the spring and applying 10-34-0, at about 225. Agronomist Tony Vyn says this illustrates the importance of continuing to use a starter fertilizer in certain situations, such as when most of the nitrogen is sidedressed.

To study this, Vyn tested Aspire, a product that contains 58% K and 0.5% boron, across four different tillage systems in corn, two of which were fall and spring strip-till. He banded 200 pounds of Aspire in both systems, while no Aspire served as a control.

In the first corn crop following Aspire, the fall strip-till system picked up about a 10-bushel yield advantage over no Aspire, while the spring strip-till saw around a 16-bushel advantage (see chart p. 16).

But yield results were even more drastic after a second 200-pound-per-acre application of Aspire in the second corn crops, which followed after a year of no-tilled soybeans. The fall strip-till then saw a nearly 32-bushel yield advantage from banded K compared to no K — 241.7 vs. 210 bushels per acre.

Where K had been banded in the spring, the yield gap was smaller. Where Aspire had been applied twice, the corn yielded 226.7 bushels, just over a 10-bushel increase where no K was applied. Vyn notes that he wouldn’t recommend spring strip-tilling for those in the Eastern Corn Belt dealing with silty clay soils.

“With high clay content and poorly draining soils, we really want to try to accomplish the strip-tillage in the fall,” he says, noting that banding high K rates close to planting is also much riskier compared to banding K in the fall because of potential salt injury to corn seedlings.

But if strip-tillers are in crop rotations that include soybeans, they still need to think about broadcasting K.

“It’s my experience that if you begin with low tests, and particularly if you’re going to switch from 30-inch corn to 15-inch soybeans, that you probably want to have a mixture of banded and broadcast potassium,” Vyn says.

Do Your Own Research

Vyn admits that there’s too little research on nutrient application specific to strip-till.

“It doesn’t address the spectrum of needs out there,” he says.

He encourages strip-tillers to reach out to their state universities and find faculty they can partner with to do their own independent research. He wants strip-tillers to consider doing on-farm research on hybrid density, stover management, soil types and different ways of applying nutrients with different timings. And he wants strip-tillers to really look at the long-term effects.

“As I pointed out, sometimes the 2-year information is quite different, and the long-term response to nutrient banding may be different than what you see in the first year.”