Every time Otwell, Ind., strip-tiller Chris Perkins breaks the 300-bushel barrier, a framed vintage DeKalb seed bag goes up on his office walls, showing the year, hybrid type and yield number. He’s running out of wall space. Five bags currently hang like retired jerseys in the rafters of a basketball arena, each representing a significant milestone and learning experience.

“This field wound up averaging 317 bushels per acre, but the end rows murdered us on that one,” Perkins says, as he points to one of the bags. “If you took the end rows away, the field averaged over 347 bushels per acre. That tells you how much damage you do by constantly going in and making applications. My wife came up with the idea of hanging up the vintage bags. They’re neat keepsakes and remind us of what we did and how we did it.”

Perkins will soon add another keepsake to his office — a plaque with the words “2024 Strip-Till Innovator” on it, an award he’s been working toward since he started strip-tilling almost a decade ago. He earned it by challenging conventional corn-growing wisdom in an area where strip-till was mostly a foreign concept and developing a systems-approach banding program capable of boosting yields by over 60 bushels per acre.

“It’s a huge honor, and you have no idea how much this award means to a lot of people, not just me,” Perkins says. “It’s not hard to look good when you have good people surrounding you.”

On top of running his family farm, Perkins also owns and operates Banded Ag, an ag research, consulting and custom application business that’s grown to over 10,000 custom spring strip-till acres in Indiana and Kentucky since he launched it in 2017. But a quarterback is only as good as his teammates, and Perkins gives most of the credit to his 6 full-time employees.

“Everything we do and everything we have, it really doesn’t have shit to do with me,” Perkins says. “It has everything to do with them.”

Innovator Origin Story

Perkins couldn’t believe it when he reached the 200-bushel mark for the first time several years ago. And going from 200 to 250 bushels was much harder than going from 250 to 300, he says. Once he developed his system, as complex as it is, growing a high-yielding crop boiled down to 4 simple steps.

“Picking the right hybrid, banding nutrition below the plant, feeding the hybrid and protecting the health of the hybrid throughout the season,” he says. “Once you start to get the hang of it, it starts becoming a lot easier.”

Perkins’ systematic approach was inspired by University of Illinois professor Fred Below’s publication, The Seven Wonders of the Corn Yield World, which Perkins calls one of the most important playbooks to ever hit agriculture.

“Dr. Below and I became friends more than 10 years ago when I cold-called his office to ask some questions about starter fertilizer, and since then he’s become my mentor in studying corn production in a systematic way,” Perkins says.

The phone call to Below sparked Perkins’ own on-farm research. He built his first 8-row strip-till bar equipped with shanks and a 1,200-pound dry fertilizer box in 2017, and started experimenting with nutrient placement, fungicide use and hybrid performance on a 52-acre test plot.

“This all started when I took a group of farmers up to the University of Illinois to visit with Fred Below,” Perkins recalls. “Fred was doing research on fertilizer placement with 20-inch corn. I’ll never forget, everyone in the group was looking at leaf structure, while I was army crawling across the ground looking at the roots. I said, ‘I think the problem is down here, not up there.’”

Perkins noticed some plants had different overall root structures in the 20-inch row spacing, leading him to question if various hybrids would react differently to banded fertility if row spacing was making that much of a difference. He tested the theory out with his own strip-till corn hybrid trials that compared 8 rows with banded fertilizer to 8 rows without it.

“The results were incredible,” Perkins says. “With some hybrids, there was no difference, no matter what we did. But with other hybrids, there was a 60-bushel advantage with banded fertilizer. I’m looking for a smaller root structure with more fine and fibrous root hairs. I’m a big believer that large, coarse roots are a function of energy, so we want what I call Goldilocks roots, not too big, not too small, but just right. I’ve come to believe large roots can cost you yield.”

“Chris has become one of the premier strip-till leaders through a long road of trial and error…” –Fred Below

Many farmers in southern Indiana were unfamiliar with strip-till until Perkins introduced them to it with the eye-opening results from his trials. Banded Ag was born soon after, and strip-till is now on the rise in the region.

“Chris has become one of the premier strip-till leaders through a long road of trial and error to complete a true banded system for not only his farm, but also the growers that he works with and advises,” Below says.

“Our customers helped build this, too,” Perkins says. “They took a risk when everyone was telling them they’re dumb and it’s not going to work. There was only 1 strip-till bar running in our area in 2016. Now there’s about 10.”

Strip-Till Cheat Codes

Perkins remembers using a cheat code to beat the Nintendo classic video game Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out! as a kid. In many ways, strip-till reminds him of that video game — with a cheat code of its own.

“I have a 30-inch, 16-row John Deere 1775 ExactEmerge corn planter with hydraulic downforce and 2-by-2-by-2 that allows us to hit the crop anywhere we want,” he says. “AutoPath has also been a game-changer, making it easy to shift rows every year. Our tractor has 2 lines in it. If it’s an even year, it will grab the 2018 line. If it’s an odd year, it will grab the 2019 line. Both lines are 15 inches off each other.”

Perkins likens his equipment to cheat codes in a video game. His Land Luvr strip-till bars are equipped with liquid tanks and dry boxes for “the best of both worlds.” His John Deere 1775 ExactEmerge planter is equipped with hydraulic downforce, AutoPath and 2-by-2-by-2 that allows for precise fertilizer placement. Photo by: Noah Newman

Perkins has 4 more cheat codes in the form of his Land Luvr strip-till bars. He has three 16-row bars and one 24-row bar, each equipped with a liquid tank and a dry box to apply dry and liquid fertilizer at the same time 7-8 inches below where the planter runs.

“Having the ability to put food for the crop directly at the bottom of the root is a cheat code,” Perkins says. “The liquid fertilizer is dropping directly on the dry fertilizer and impregnating it on the go. My goal is to apply 10 gallons per acre of a liquid mix to complement the dry mix. Some people depend solely on dry or solely on liquid fertilizer. Why not take advantage of the best of both worlds? I’m using humics, fulvics and sugar to create an energy drink for the soil biology below.”

Perkins’ banding mix consists of nitrogen (N), phosphorous (P), potassium (K), sulfur, zinc and boron. He says it can be tweaked up or down, but typically it remains about the same.

The old “1 pound of N per bushel of corn yield” needs to go because it’s wrong, Perkins says. He shoots for 0.57-0.63 pounds of applied N per bushel of corn and sees conventional field-wide fertilizer application as wasteful. Perkins urges strip-tillers to focus on the actual amount of N required to produce a bushel of corn and apply it where it will do best in the root zone.

“We’re around 600 pounds per acre of applied nutrients representing our entire program…” – Chris Perkins

“We have to realize we’re feeding the plant, not the soil,” Perkins says. “We place all of our nutrients for the year up front in the spring-built berms and watch it carry through the growing season with no sidedressing. While I don’t always share my exact fertility program, I can tell you that each year we’re around 600 pounds per acre of applied nutrients representing our entire program.”

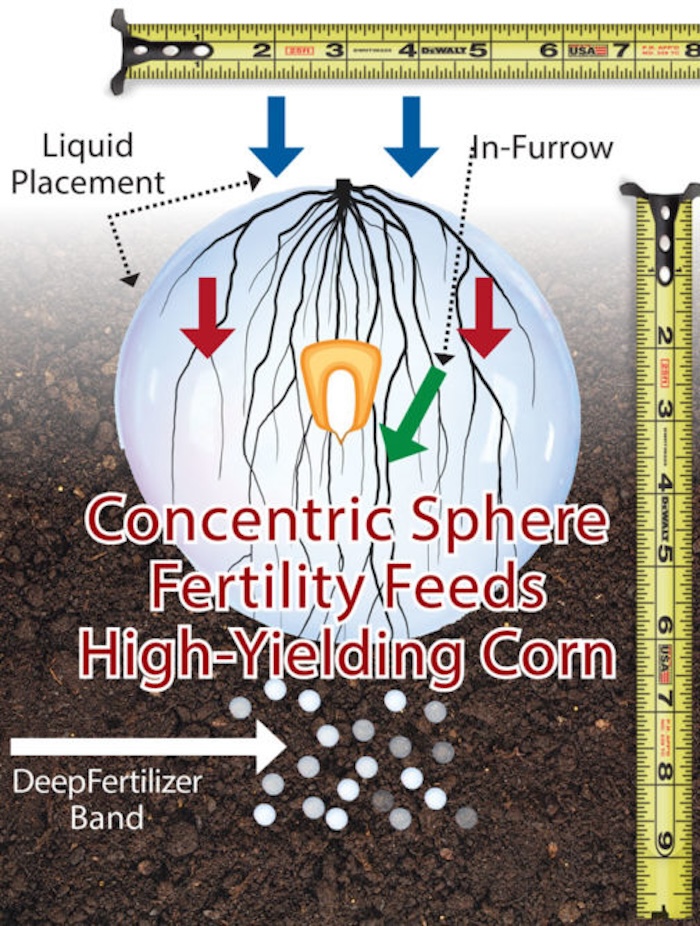

Perkins likens his system to an IV placed directly below the plant, providing a balanced food source for the roots throughout the summer (see Concentric Sphere Fertility sidebar for more details).

‘Concentric Sphere Fertility’ Wins Nutrient Relay Race

By Dan Crummett, Contributing Editor

Chris Perkins says his years of observation on banded fertilizer and corn production have convinced him to view plant uptake of nutrients throughout the season as a relay race, rather than as an early season farming chore.

“A track coach will usually put the fastest runner on the fourth leg of a four-runner relay to take advantage of the explosive speed that runner can provide after the other three racers have established and held the position,” Perkins says.

“I think it’s the same with corn production. A lot of folks put down pre-plant fertilizer and plant with a starter solution and see a very good stand emergence. Most go on to sidedress as the corn plant matures vegetatively. But we’ve found corn needs nutrients available when it enters and progresses through the reproductive stage, too — the point in the crop’s life when it’s making the weight that leads to profitable production.”

Perkins’ business associate, Chris Kasten, data analyst for TEVA Corp., says corn accumulates nearly ¾ of its total vegetative weight before it ever produces what the farmer sells.

“Not providing sufficient plant nutrients throughout the growing season is like having the fastest car on the track and allowing it to run out of gas before the race is over,” Kasten says. “A lot of folks ignore this part of the season and don’t produce as much corn as they could if they had used additional, well-placed fertilizer.”

Considering this, Perkins envisions what he calls the rhizosphere relay, a concept that imagines a sphere of soil beneath the corn plant in which the roots operate from emergence through senescence after harvest.

“I call it Concentric Sphere Fertility and use it to make nutrients available throughout the growing season,” Kasten says. “It places nutrients in strategic position to leverage root growth and the natural downward migration of nutrients in the soil over time.”

Perkins says using the spherical approach to fertilizer placement around the seed’s emerging roots mimics the track-and-field relay metaphor.

“When we band fertilizer pre-plant with the strip-till rig, we’re placing nutrients at the bottom of the sphere 7-8 inches deep,” Perkins says. “The in-furrow application at planting puts nutrients close to the emerging radicle and new roots of the seed at germination. At planting, a 2-by-2 application leaves nutrients on both sides of the seed in the sphere below ground. If we put tubes on the back of the planter and spit fertilizer out the back of them, we fertilize the very top of the sphere. So as nutrients move down, they are always in contact with where the roots are going, and we hit each one of those relay handoffs throughout the season.”

Perkins says Concentric Sphere Fertility places nutrients in the majority of soil volume in the feeding zone of the corn plant.

“It is imperative to concentrate on the rhizosphere for the feeding mechanics of plant nutrition,” Perkins says. “This sphere fertility concept takes that into account for each relay leg of this race.

“The in-furrow is right there at the seed. That’s your first runner in the relay. Then you’re going to enter the percolation zone from the dribbled-on nutrients on the back of the planter, followed quickly by the 2-by-2 application. By the time the plant begins to enter the reproductive stage, the deep-banded pre-plant has already come into play to finish out the race.”

Healthy Crop, Healthy Residue

Even more valuable than fertilizer is the residue that comes from a high-yielding crop. The proof is in the soil tests, which Perkins conducts on his corn-on-corn fields every February or March when the soil temperature reaches 52-53 degrees F. Perkins uses saturated-paste tests, rather than traditional acid-based tests, because plants take up nutrients in water-based solutions, he says.

Even though Perkins isn’t spreading fertilizer across the entire field, the tests showed that sulfur, P and K levels increased every year from 2019 to 2023. Sulfur went up from 25 pounds per acre to 45, while K increased from 267 to 529 pounds and P increased from 15 to 78 pounds.

“A good crop will grow you an even better crop the following year,” Perkins says. “There’s a huge difference between 250-bushel corn residue and 300-bushel corn residue.”

Perkins’ strip-till banded rows (L) show a distinct difference from the rows under a conventionally managed fertility program (R) during the early growing season. Photo by: Chris Perkins

“A 300-bushel corn crop produces residue that’s good for about 135 pounds of N, which is the equivalent of 293 pounds of urea; 48 pounds of P205 phosphate or 92 pounds of monoammonium phosphate; 330 pounds of K2O or 550 pounds of potassium chloride; and 21 pounds of sulfur, equivalent to 87.5 pounds of ammonium sulphate,” says Chris Kasten, business associate of Perkins and data analyst for TEVA Corp. “That far exceeds most growers’ entire fertility program for their corn crop, and that’s just in the residue of what Chris is growing.”

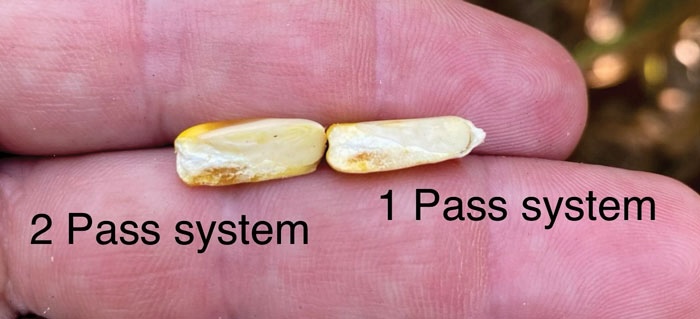

Managing residue from a high-yielding crop is always going to be a challenge. But Perkins finds success with a John Deere StalkMaster row unit for his combine that enables a high level of residue processing. He’s also noticed the healthier the residue, the better it breaks down and gives back to the soil. That’s where fungicide comes into play.

“When we did fungicide trials in the year of the southern rust disaster of 2016, the corn that didn’t have fungicide produced 80-100 bushels less than the corn that did have fungicide,” Perkins says. “Then a couple months after harvest, the corn without fungicide looked like it was just combined the day before. It had nothing to give that the soil biology wanted. It was junk. But the corn that had the fungicide and the makeup of a healthy crop was degrading and breaking down into the soil. That’s when I realized, there’s more to fungicides than just keeping plants healthy. They also help with decomposition later to get the next crop going.”

“A good crop will grow you an even better crop the following year…” – Chris Perkins

Perkins’ program calls for a minimum of 2 fungicide applications throughout the growing season, and some acres even get a third application if it’s worth the ROI.

“Stressed plants give off ethylene (a naturally produced gaseous plant hormone responsible for tassel and silk drop, yellowing leaves and leaf drop in corn at the end of the season) and send it throughout the canopy to adjacent plants, which is a problem,” Perkins says. “We want to keep the plants green and thriving as long as we can throughout the season for the maximum development of kernels. The fungicides help us accomplish that.”

Perkins had one of his biggest breakthroughs when he realized there’s more to fungicides than just crop protection. The kernel on the left is the product of a 2-application fungicide program, while the kernel on the right had a single application. Photo by: Chris Perkins

What’s Next?

Like a true innovator, Perkins never stops looking for ways to improve. He’s always studying the latest trends, and right now that includes cover crops. Although cover crop adoption rates are up in his area, Perkins isn’t quite ready to hop on board.

“I’m not saying people using cover crops are right or wrong — I’m just sitting back and studying them right now,” Perkins says. “Are we using a cover crop because it’s making everything healthier? I can buy that, and I’ll have that conversation. Or are we doing it because it helps hold the ground in place? I’ll have that conversation, but really good corn residue will hold the ground in place just as well as anything that I pay to plant.”

Perkins says he’d consider cover crops if he can come up with an efficient way to plant them while not interfering with his strips.

“I’m wondering if I could build the planter to offset rows where the strip-till bar is so I could plant cover crops and leave a strip that will be clean for me the next spring. I do have some interest in that,” Perkins says.

He sticks with what works but is never afraid to pivot when an opportunity presents itself. Perkins is planting soybeans, somewhat reluctantly, for the first time after a retiring customer asked him to take over his farm.

“I didn’t want to have 1,500 acres of corn on corn, but I also didn’t want to buy a soybean planter, so we’re doing 30-inch soybeans,” Perkins says.

He almost pulled the trigger on a 20-inch planter at an auction, but he says he “didn’t have the guts to do it.” A 20-inch planter would make it easier to plant both corn and soybeans, and Perkins believes it’s only a matter of time until 20-inch corn becomes standard.

“I think 20-inch corn is the future, especially when short corn comes out,” Perkins says. “Right now, on my farm, we typically average 38,600 seeds per acre. With short corn hybrids, you’ll be able to push plant populations to the upper 40,000 or lower 50,000 range, and really start hitting stride on yield.”

At the end of the day, Perkins focuses on what works best for his soils. While the Banded Ag system is successful in his region, there’s no guarantee it would work the same in California or Pennsylvania because no one size fits all in strip-till. He urges farmers to keep that in mind the next time they hear a presentation or new product pitch from a salesperson.

“Take biologicals, for example,” Perkins says. “I have nothing against them, but I’ve never understood wanting to introduce something that’s not native to my soils. My soil might be a little different than some guys in California or on the East Coast. We just try to promote what we have in the ground now.

“I remember thinking my whole life, ‘If only we farmed in central Illinois.’ Now I’m saying, ‘I don’t know if we want to be farming there with what we’re doing.’ It’s a drastically different world to learn wherever you go.”

Click here to watch the 2024 Strip-Till Innovator Video Series.