LESSONS LEARNED. ARS plant physiologist Jerry Hatfield if strip-tillers start looking in that soil and at plant-to-plant variation, there is a lot of variation that is induced by tillage. Early season plant vigor is the reason strip-till is successful in this regard, he says.

Dr. Jerry Hatfield, who runs the National Laboratory for Agriculture and the Environment, a USDA Agricultural Research Service (ARS) facility in Ames, Iowa, says soil resources and weather are changing rapidly.

“The last few years of weather data lay on the fringes of what we’ve experienced in the last 120 years,” he says. “We see that across all the Midwest and we can expect this trend to continue.”

Hatfield has done extensive research on the interactions within the soil-plant-atmosphere spectrum and their connection to air, water and soil quality. His recent research examined the correlation between early-season nutrient applications on plant health in strip-tilled corn and its impact on yields.

It’s his belief that farmers need to rethink their approach to soil degradation.

“We underestimate degradation, and we think if we apply more nitrogen (N) or other nutrients or till the soil more, all of our issues will be over but that’s not what happens,” Hatfield says. “Yield is not necessarily the measure of how efficient our systems are. Profit is the ultimate measure of efficiency.”

Because they wanted to start promoting no-till and reduced tillage practices, the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship asked Hatfield and his team to extensively compare tillage systems across Iowa. Pulling data from 8 counties throughout the state, Hatfield had several initial observations.

“No-till and reduced tillage corn yields were somewhere in the average of 20 to 30 bushels above county average,” he says. “The yield increase over time is actually much steeper than the county average, too. So not only have those tillage systems yielded more, the methods have really started to express themselves.”

In comparing conventional tillage (fall and spring), fall strip-till and no-till, Hatfield surmised that no-till and strip-till are superior to conventional tillage when stacked against the ecological pressures of the future. In a presentation at the 2016 National Strip-Tillage Conference, he outlined three specific challenges farmers face in the future, and explained how each stack up against different tillage methods.

Changing Weather

Although there is much debate about climate science, Hatfield says recent weather patterns have broken from past trends and will become even more unpredictable in the future. If weather follows the course it seems to be on, rain events will become more intense and more infrequent, he says.

“We need a tillage system that will handle the extremes in precipitation,” says Hatfield. “I can tell you that conventional tillage systems are not going to handle that because most of the erosion I see and runoff I see are coming out of those systems, because they slake very quickly and don’t have any protection.”

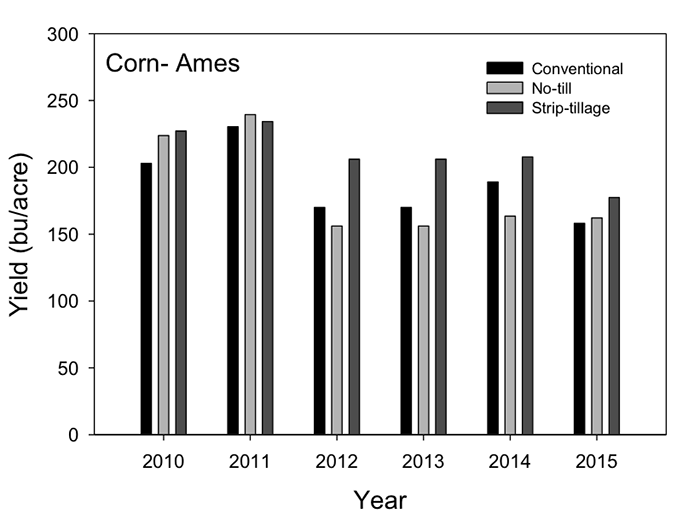

CONSISTENTLY CONSISTENT. In Hatfield’s tillage comparison studies throughout Iowa, he found that strip-till yields were the highest and most consistent. He found strip-till to be a superior system for handling conditions like exceptionally dry years (2012) and exceptionally wet years (2013) due to rooting dynamics. =

Hatfield points out that seasonal rainfall may mean much less to farmers if only a small portion of it infiltrates their soil. The aggregate soil structure created by strip-till is conducive to infiltration, he says.

“It’s not enough to say that I got 2 inches of rain,” Hatfield says. “If you got an inch of runoff from 2 inches of rain, you only got 1 inch in the soil. It also contributes to soil degradation. I see soil running off fields with less than an inch of rainfall. If we’re going to pick up rain events that dump 2, 4, 6 or 8 inches in a 24-hour period and the soil can only absorb 1 inch, everything else is gone and it’ll carry soil with it.”

Hatfield’s research showed that the strip-tilled plots he studied saw the largest advantage over conventionally tilled fields in exceptionally dry years such as 2012 and exceptionally wet years like 2013 due to rooting dynamics.

Less Yield Variation

Hatfield’s research also showed strip-till had the most even emergence among tillage methods and that no-till and strip-till had the least overall variation in yield across soil types.

“We often look at yield variation across the whole field and we know that poor soils have lower yields than good soils within those fields,” he says. “If you start looking in that soil and at plant-to-plant variation, we find that there is a lot of variation that is induced by tillage.”

Early season plant vigor is the reason strip-till is successful in this regard, he says.

“When going to a spring or a fall strip, we get a much faster and more vertical root development as opposed to the horizontal development we’ve seen with conventional tillage,” says Hatfield. “What happens with strip-till is the plant responds to the conditions which tend to be a little bit drier in that system. So, the roots go down farther.

“We’ve seen roots grow three times faster in a vertical direction than in conventional tillage. That’s also another way in which strip-till weatherproofs itself.”

In his studies, Hatfield did extensive emergence testing across tillage methods. The results, as with yield, showed less variation.

“We also observed among the tillage methods, emergence was fairly even, but the difference was in the rate and uniformity,” Hatfield says. “We did stand counts at all our sites and we had good stands, but what was happening in our strip-till systems was faster and more uniform emergence. The strip-till systems saw emergence within one day. With conventional tillage, we’d see plants emerge over a 3- to 5-day period.”

Nutrient, Water & Gas Interaction

As weather and environmental conditions change in the future, applying an increasing amount of fertilizer in hopes of higher yields will likely give way to focusing purely on the efficiency of nutrient uptake because that is where profits lie.

Hatfield says his research shows that strip-till is the best suited for this efficiency because it creates a zone where there is effective water, nutrient, light and gas exchange.

“Plant roots beneath the surface are just like you and I, they need oxygen to perform,” he says. “We have to have the soil structure in such a way that water and oxygen go in easily and CO2 comes out.”

Tillage can be an interrupter of this smooth exchange or it can assist with it, Hatfield points out.

“Tillage interacts with water, oxygen and nutrient supply,” he says. “What we’ve seen with strip-till is that it improves the efficiency of these exchanges rather than restricting them.”