No-till farming became a way of life early in the rolling hills of western Kentucky. Growers there, eager to protect their fragile soils, began to adopt the practice pioneered by local farmer Harry Young, who planted his first no-till crop in 1962. Spurred by University of Tennessee research and annual demonstrations at the nearby Milan No-Till Field Day, farmers in the area rapidly parked their plows.

“No-till became the way to farm with the efforts of Howard Martin and others developing equipment needed to make the practice successful,” says Jeff Morgan, western regional manager at H&R Agri-Power, a large Case IH dealership based in Hopkinsville. “Until about 2010, growers had tuned their management to grow respectable corn yields in rotations with wheat and soybeans. By 2010-12, however, we’d reached a yield cap with the practices we’d been using for so long, and we knew we’d have to change something.”

That something involved an abrupt shift to strip-till’s limited soil disturbance and the ability to better place fertilizer within easy reach of crop roots. Within 6 years, a 150-mile stretch from Hickman, near the western tip of Kentucky, east to Bowling Green adopted strip-till on about 6,000 acres, particularly in more level fields. The rapid growth of strip-till in western Kentucky also jumped the state line into western Tennessee as word spread of the economic benefits of strips and banded fertilizer.

How It Happened

Agricultural practices are continually changing everywhere, but strip-till’s blitzkrieg-like performance in western Kentucky is certainly the material for behavioral science research. Morgan says it was a classic community effort.

“The producers in this area are on the leading edge as far as embracing new practices and taking calculated risks,” Morgan says. “They banded together as a brain trust in search of answers to the yield dilemma.”

COVER MODIFICATION. For several years, the Lesters have used an on-farm modification to their Kuhn Krause Gladiator to plant 2 rows of cereal rye between strips. The Gladiator runs a pair of single- coulter openers fed by their air seeder.

In 2014, one of those forward-thinking farmers drove to Cedar Rapids, Iowa, for the first-ever National Strip-Tillage Conference. Morgan says the farmer came back very excited about what Corn Belt strip-tillers were doing, but he knew that Kentucky growers would have to carefully adapt strip-till to their conditions.

“All of us realized no one had all the knowledge and experience to tell us what to do, and as growers and input providers, we’d have to work together,” Morgan explains. “We had the fertilizer and crop consultants willing to work with growers, and the groups began collaborating with one another, talking, sharing experiences about mistakes and successes, and that accelerated the learning curve.”

By the 2016-17 growing season, H&R Agri-Power decided to support the effort by making strip-till equipment available on a rental basis to give growers a chance to experiment with the practice without the initial high cost of purchasing equipment.

“We were confident in what strip-till was doing in other regions, and we wanted to put a safety net under our growers as they learned to adapt,” Morgan says. “We were promoting a process, not brands, so there were several brands of strip-till bars involved. We just wanted to get them in the fields so our farmers could learn how to use them.”

The company also put a strip-till rig and fertilizer cart in the hands of a seed dealer/crop consultant for two seasons and told him to “go play,” doing test plots and custom work with corn and soybeans — with and without fertilizer. H&R asked the consultant to use his imagination when experimenting and then share his experience with others. Morgan says the project worked very well and added valuable information for growers in the area.

The dealership also launched a series of meetings across the area to introduce the practice, and Morgan was amazed at the level of interest.

“Strip-till has improved yields enough for growers to pay for the investment in equipment…”

“The first meeting was in Hopkinsville, and we invited 15 local producers,” Morgan says. “Forty people showed up! We just promoted the meeting and let the brain trust put the meat on the bones of the program.”

The group went on to hold another meeting 70 miles west, based on the model of the Hopkinsville gathering, and observed more interest and excitement about strip-till from growers in that geography. Since then, the group has continued to grow, and efforts have expanded into the cotton country of western Tennessee.

The success hasn’t come without hurdles. Morgan says one of the biggest is the lack of local history with strip-till.

“We are having to learn what to do with concentrated fertilizer rates since we’re no longer broadcasting as we did with no-till,” Morgan says. “How do we measure and manage carry-over, and how do we adjust for various row spacings?”

Morgan says answers to those questions are coming as the various groups involved meet and collaborate.

“We put our heads together and say this seems logical — let’s test it and try it and then roll the dice as a group,” he explains.

Initial Results

Morgan describes himself as a farm machinery person, but he says if he had to explain what growers want, he’d say simply a good environment for seed to germinate and a good road for the planter to run on.

Morgan says western Kentucky growers were quick to realize strip-till provides both, plus the opportunity to penetrate the no-till-only yield cap and take care of the land.

“Growers found that after building strips in the fall, planting conditions in the strips were very conducive for germination and seed growth,” he says. “Strip-till’s deep tillage — usually about 7 inches in most western Kentucky fields — helped yield response, along with improvements it allows in fertilizer placement.

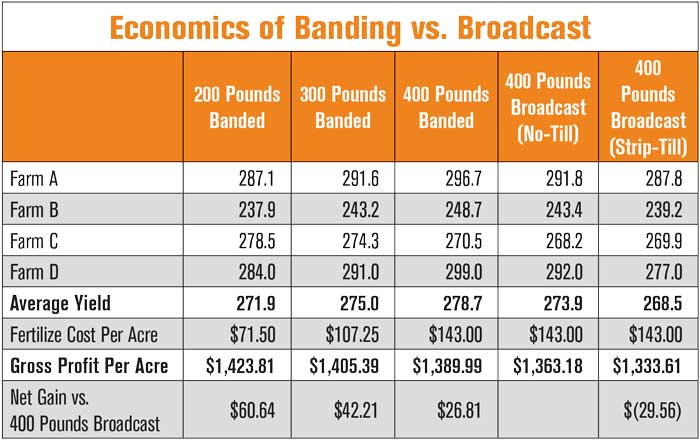

Jesse Little, who operates Little Seed Co. in Mayfield, Ky., compared 200-, 300- and 400-pound banded fertilizer rates with 400-pound 9-23-30 broadcast rates on no-till and strip-till fields in western Kentucky. He found banding increased per-acre profits from about $27 to more than $60.

“In addition, incorporating cover crops into their management is allowing growers to expand strip-till onto marginal acres where they once feared any tillage would increase erosion.”

Incorporating cover crops is a more advanced management consideration than the group initially tackled. From 2015-20, they took baby steps, testing one practice at a time.

“They built strips and didn’t play with fertilizer at first,” he explains. “They got comfortable with strips and managing erosion, and then started testing fertilizer with and without cover crops.”

Today, Morgan says he’s amazed at the increasing interest in strip-till.

“Over the last 2 years, we have had people knocking on the door saying they’re all in and want to move to strip-till and deep-placed fertilizer and do it all at once — no going slow,” he says. “So far, the results have been very good. Our growers and consultants have done some phenomenal things.”

Strip-tillers in the area are consistently making back-to-back 180-220 bushel-per-acre corn on their thin, low organic matter topsoils.

“Overall, strip-till improved yields enough for growers to pay for the investment in equipment, and they will tell you it’s been worth the trouble,” he says. “This will drive sustainability into the future, just as no-till did many years ago.”

The Real Money

Jesse Little, part of Morgan’s strip-till brain trust, operates Little Seed Co. in Mayfield, Ky., as a Pioneer agent. His work extends over 9 counties in western Kentucky, and he has a dozen 10-acre research plots in his network of cooperators that he services with a renovated 6-row planter.

Little says the real money in strip-till comes from improved placement of fertilizer. His research shows consistently high fertility rates in the top 2 inches of cooperator’s topsoil, with very little of the nutrients found in the 4-6 inch layers.

“This is a product of years of spreading non-mobile fertility on the ground,” he says. “We’re finding only 30% of the phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) at 4-6 inches. Banded fertilizer applied through the strip-till rig puts these nutrients much closer to the root zone of the crop and allows for significant reductions in applied fertilizer.”

STRIP ADVANTAGE. One month after planting, this year’s strip-till soybeans at L&C Farms showed tape-measure estimates of nearly 50% taller and wider (left) compared with an adjacent no-till plot planted the same day (right).

Banded fertilizer is a gain in efficiency that helps net income on the farm, according to Little’s field trials (see table on p. 19). In 2022, he compared 200-, 300- and 400-pound banded fertilizer rates with 400-pound 9-23-30 broadcast rates on no-till and strip-till fields. The trials were on adjacent plots within fields at 4 locations.

Little used harvested yields from those plots to show the economics based on the price of fertilizer, yields, current commodity prices and in-pocket gains.

“The banded treatments were all more profitable than either broadcast treatment, with increased per-acre profits ranging from nearly $27 to more than $60,” he says.

While 6,000 acres of new strip-till fields is a significant amount, particularly considering how quickly it came to be, Little says the rolling hills of western Kentucky are only moderately productive compared with the Corn Belt.

“In my experience, the poorer the soil quality, the more erosion is a problem,” Little says. “About 80% of our acres here are fairly rolling, making some areas not feasible for strip-till. Still, we have several growers who have purchased strip-till equipment and have adopted it across their whole operation with great success.”

Kentucky Strip-Till in Practice

One of those growers is Micah Lester, who operates the 7,000-acre Lester Family Farms with his father, Gary, west of Hopkinsville. Lester says they harvest about 11,000 acres every year by planting half the farm in corn and half in double-crop wheat and soybeans. The Lesters started strip-tilling in 2013 — the same year they adopted controlled-traffic farming and cover crops.

“That move also meant we had to upgrade our John Deere guidance technology to keep everything on track throughout the season, so it all worked together as a 3-pronged approach,” Lester says.

All the Lester corn is strip-tilled, and soybeans follow wheat as a double crop. Much of the fertility for the wheat, beans and following year’s corn goes on via spreader truck before the wheat. Then, as the season develops, the corn crop is monitored and spoon-fed nitrogen with sidedress applications, while wheat is top-dressed according to growth patterns and weather conditions.

The Lesters use a John Deere 9520RX with tracks to pull a 16-row, 40-foot Kuhn Krause Gladiator strip-till rig equipped with shanks and a track-mounted Montag Gen II twin-bin fertilizer system. The Gladiator has modified row cleaners to make them more aggressive, along with bolted angle-iron on the shanks to increase the “blow out” of residue.

“If we’re stripping behind single-crop beans, there’s not much trash, but with double-crop beans, we’re dealing with corn residue, wheat from the summer and last fall’s bean residue,” Lester says. “The more aggressive setup just helps us provide a cleaner strip that dries out and warms up quickly when it’s time to plant corn.”

While they are working with Martin-Till to develop a seeding system for the Gladiator, the Lesters are currently using a cover crop seeding system on their air-seeder to plant 2 rows of cereal rye between 30-inch corn rows.

“We use the 2 boxes on the Montag to carry diammonium phosphate (DAP) and rye,” Lester says. “We use about 50 pounds of DAP in-row per acre to boost the rye’s growth. We have to terminate in April, so we have to get growing quickly. We’ve also added a third Salford tank between the Gladiator and the Montag to carry dry zinc to put on top of our rows because it’s much cheaper than liquid zinc applied 2-by-2.”

Strip-till offers the best of both worlds between no-till and conventional farming for their operation. Lester says they liked no-till, but it was never warm or dry enough in the spring for proper planting — an issue that’s been solved with the switch to strip-till.

SPRING STRIPS. Near Brighton, Tenn., Leslie Stewart and his brother, Chad, jumped into strip-till in the fall of 2021, building strips to see how they would fare through the winter. Heavy rains settled them significantly, so the brothers refreshed the strips in the spring and banded their phosphorus and potassium just ahead of the corn planter, saving a third of their usual broadcast rate.

“It’s better to till 6-8 inches with the Gladiator every 30 inches and leave undisturbed soil between rows to provides better water infiltration and tilth,” Lester says.

Strip-till proved itself in the cold and wet season this year. The Lesters planted corn April 27 — the latest planting date ever — but the strip-till ground was in good shape.

“The no-till fields were still heavy, wet and cold,” Lester says. “Conventional farmers weren’t happy, but we were.”

The Lesters save money by not applying dry fertilizer and cutting herbicide costs thanks to the rye cover crop. Lester says they’re not leaving out a full chemical application, but the rye helps them get by with less by holding down the weeds.

“We aren’t using test strips in our corn, but I can tell you I’m making more corn than I’ve ever made and saving money on inputs at the same time, even though we have some higher input costs because of the technology and cover crops,” Lester says.

Cotton Country Savings

About 45 minutes northeast of Memphis, Leslie Stewart and his brother, Chad, operate L&C Farms near Brighton, Tenn. They are new strip-tillers growing 30-inch corn and 60-inch skip-row cotton.

“We bought a 12-row, 30-inch Gladiator last fall to break up some compaction and wanted to see how the strips settled over the winter,” Leslie explains. “The strips ran about 8 inches deep and provided quite a challenge for our 420-horsepower Steiger tractor. We need more horsepower to pull like we want to, but right now we’re experimenting with ballast to address the problem.

“When we bought the Krause, we didn’t want to invest in the fertilizer system at the time, so this spring we ran a 2-bin Montag system with the strip-till rig, just ahead of the planter.

“I worried about how that would work, but even with some heavy rains on the strips we’ve had no problems,” he says.

Ultimately the brothers say they were able to cut their broadcast fertilizer rate by a third on corn with banded placement.

“We’ll save even more on our 2-in-1 skip-row cotton because we’re not broadcasting across 60-inch gaps,” Leslie adds. The brothers plant two 30-inch cotton rows between 60-inch middles. “There, we’ve been able to cut our fertilizer rate by two-thirds.”

The Stewarts say their biggest problem has been trying to keep the planter on the strips, but they say their Case IH consultants are quick to help work out any GPS kinks. Also, their planter and the cotton picker don’t match, so challenges remain to get strip-till applied seamlessly across the farm.

“If I go to a 16-row strip-till bar, it may help,” Stewart says. “I may upgrade to that. Also, I want to put the Montag system on tracks. Overall, we like what we see and plan to stick with it.”