By Tom Barber, Jason Norsworthy and Tommy Butts

Figure 1. Palmer amaranth survivors following three applications of glufosinate in Mississippi Co.

Last summer an article was written about two fields of concern in Mississippi County where three applications of glufosinate failed to control Palmer amaranth. Upon first observation of these fields, a familiar sinking feeling started to appear. These left-over pigweed plants were in only a few spots (Figure 1 ) across each field and appeared to be the result of seed from a surviving mother plant the year before. Usually, if resistance is occurring it will be in small spots across the field or in a combined pattern from harvest the year before. These two fields had that “look” and were very suspicious, to say the least.

Areas of live plants were flagged in each field, and as stated in the earlier post, plants were soaked with 2% solution of Liberty and evaluated ten days later. At time of evaluation, few plants were dead in the area that had been sprayed earlier. Seed was collected from both field sites from matured plants for screening in the greenhouse over the winter in Fayetteville, AR.

Evaluating Samples

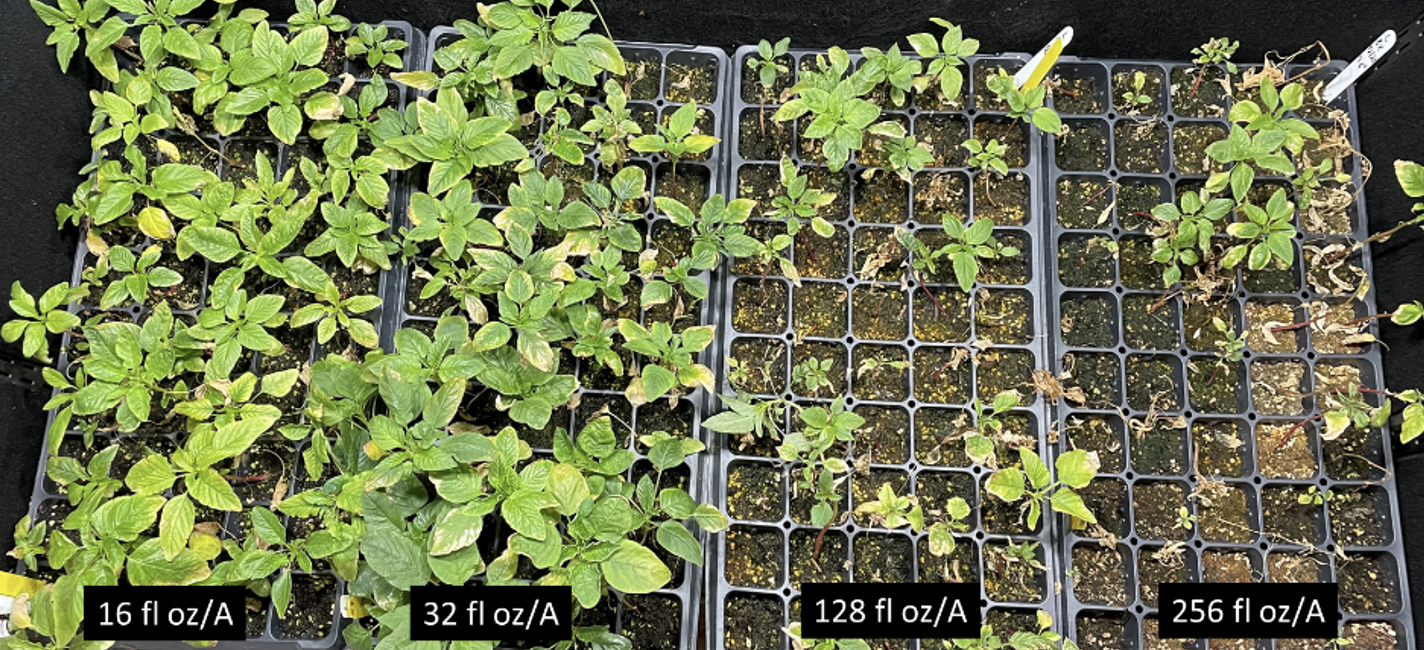

Dr. Jason Norsworthy’s weed science program at Fayetteville, Ark., has evaluated both samples from Mississippi County along with another sample collected the previous year from Crittenden County (Figure 2). Initial greenhouse experiments involved a rate response study to evaluate glufosinate effectiveness on these samples. Initial results indicated that 32 fl oz/A Liberty (glufosinate) was not providing control in the greenhouse and furthermore survivors were present following applications up to 256 oz/A (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Palmer amaranth survivors following 5 applications of glufosinate in Crittenden Co.

Figure 3: Glufosinate rate response on a Mississippi County Palmer amaranth population.

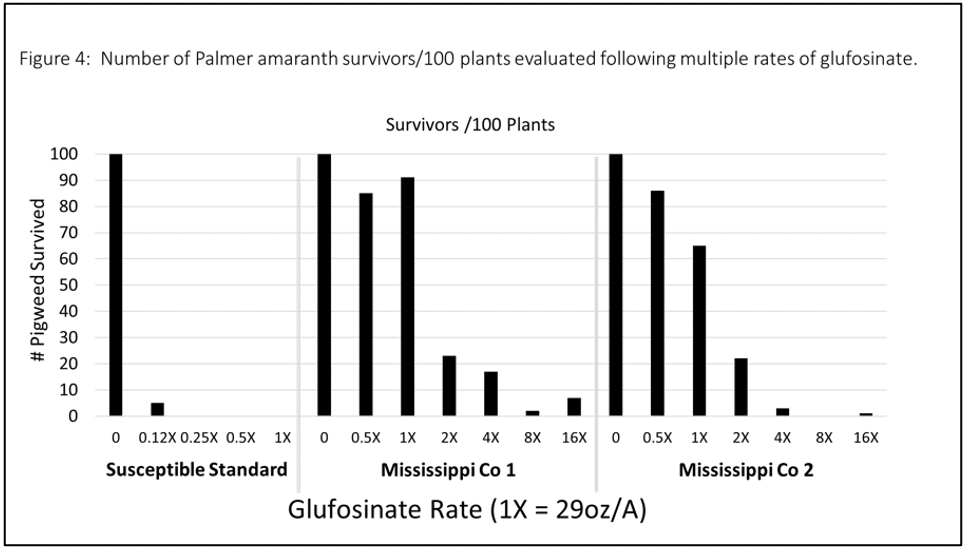

Figure 4: Number of palmer amaranth survivors/100 plants evaluated following multiple rates of glufosinate.

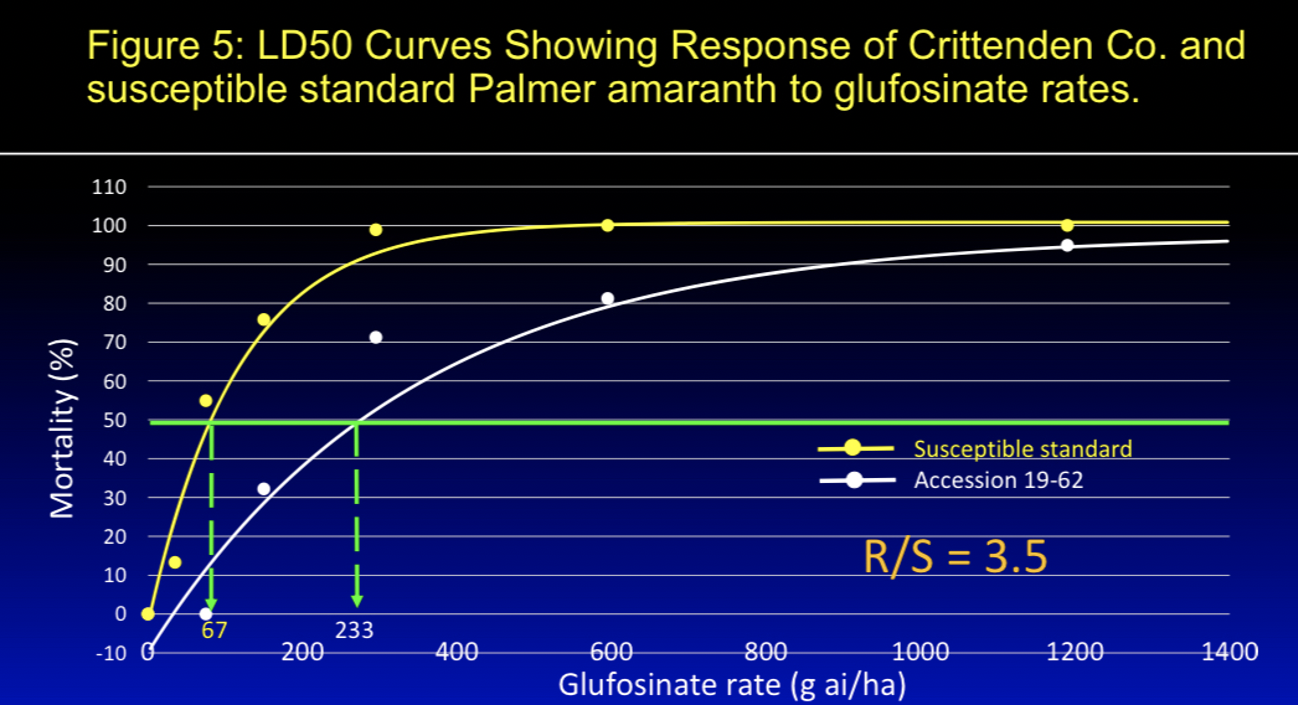

Figure 5: LD50 Curves Showing Response From Crittenden Co. and susceptible standard palmer amaranth to glufosinate rates.

According to Ian Heap’s International Resistant Weed Database, only 4 weeds in the world have developed resistance to glufosinate, including perennial ryegrass (New Zealand), rigid ryegrass (Greece), Italian ryegrass (New Zealand, Oregon and California) and goosegrass (Malaysia).

This finding will represent the first documented case of broadleaf resistance to glufosinate herbicide in the world.

It is not a big surprise that Palmer amaranth has developed resistance to glufosinate considering the history. Cotton producers have heavily relied on glufosinate since 2007, where widespread occurrence of glyphosate (Roundup) resistance was present in pigweed populations across this geography. Twelve or more years of selection pressure due to glyphosate resistance in Northeast Arkansas has placed tremendous stress on several key herbicide modes of action including glufosinate.

Pigweed Prognosis

Further testing is currently underway to determine if there is multiple-resistance to other herbicide modes of action in these three populations. Currently, this problem does not appear to be widespread across Mississippi and Crittenden county or the Northeast, Arkansas area based on extensive screenings that have been taking place in this geography. Although it stands to reason that several other fields likely contain small segments of the Palmer amaranth population that has reduced sensitivity to glufosinate.

Special care should be taken in the future to remove any escaped pigweed populations prior to seed set, regardless of crop grown in the field. In addition, we are recommending that these fields be rotated to corn if possible due to the herbicide alternatives available in a corn production system. These populations have also been screened with dicamba (Engenia). At this time, it appears dicamba has good activity on two of the three glufosinate-resistant populations. Growers who will not rotate from cotton or soybean, should strongly consider the Enlist system as a technology rotation because Enlist One plus glufosinate continues to provide the most consistent control of emerged Palmer amaranth following a single application. Applying multiple residuals at planting such as Brake + Cotoran in cotton or metribuzin + Group 15 (Anthem/Zidua, Dual Magnum, Outlook etc.) in soybean is HIGHLY recommended, regardless of the technology planted, as well as overlapping group 15 residuals POST to reduce Palmer amaranth emergence throughout the season.

Unfortunately, all of these suggestions are short-term solutions. A long-term solution for pigweed control in Arkansas will require multiple cultural tactics including deep tillage, cover crops, crop rotation, hand weeding and harvest weed seed control to reduce selection pressure from current herbicides and increase focus on pigweed seed bank reduction. Our neighbors in Tennessee have identified dicamba-resistant pigweed and it stands to reason scattered populations also exist in Arkansas. There is currently now more than ever a dire need for development of a new herbicide mode of action for pigweed control in Arkansas.