Data showing increased yield potential & ability to suppress weeds should outweigh concerns about economic barriers, says agronomist Jim Stute.

Jim Stute, an independent research agronomist in East Troy, Wis., understands that incorporating cover crops into the annual rotation can be a daunting process for a strip-tiller who’s never worked with them.

“I’ve been working in the cover crop arena since 1989, and with all that experience, I still have more questions than answers,” Stute says.

Stute is particularly interested in perceived financial barriers to implementing cover crops, as well as the economic impact they have for farmers who plant them. “People are worried about the economics — whether it’s yield reduction, added expense of the cover crop or implications related to weed control,” Stute says. “That’s really the heart of my research and outreach program now.”

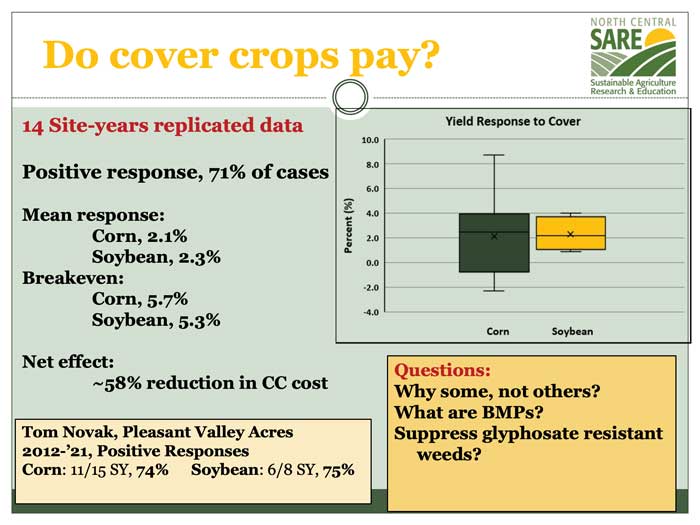

YIELD SIGN. Data shows a positive yield response to cover crops was present 71% of the time with corn and soybeans over 14 site years.

Stute has been managing his family’s farm in southeastern Wisconsin for nearly 30 years. He grows corn and soybeans, and the farm has been fully no-till since 2003. Although he has comfortably embraced cover crops on his farm, Stute understands that, for many farmers, concerns about the financial impact are the primary justification for their decision not to venture into cover crops.

“My motivation for cover crops on my farm is strictly tactical, and it’s adaptive management,” Stute says. “How do we deal with extremes in precipitation? There’s a lot of anecdotal evidence out there, but people want to see data.”

He cites fear of yield reduction, added cost and time commitment, complications related to weed management and increased risk as valid reasons farmers have for shying away from cover crops.

“What’s really interesting is that cover crop users say the exact opposite,” Stute says.

According to Stute, SARE cover crop research shows that many farmers have seen a yield increase thanks to their cover crops, even in a drought year.

“Corn was up almost 10%, and soybeans were up almost 12% in the drought year of 2012,” Stute says. “Cover crop users get improved weed control and can cut input costs, including herbicide.”

Show Me the Money

Another common concern among farmers is the possibility that they will lose money while implementing cover crops. He says they’re worried about a nonprofitable transition period, and that concern is particularly heightened among strip-tillers who work on rental ground.

“If there’s a perception that there’s a transition period and you’re going to have a yield loss initially, why would you do it?” he says. “Why would you want to improve the soil on rental ground when you know you could be outbid and lose the lease? One of the things I’m keenly interested in is showing we can have a yield impact the first year.”

In a financial analysis Stute conducted with his team, he examined two practices side by side — farmers who already use cover crops and farmers who don’t.The primary difference he had to account for in this study was in the cost of the cover crop, which includes seed cost, establishment, management, clipping and termination.

“We also looked at the yield increase and the cost of that,” Stute says. “If you have a yield bump, that’s free money, right? No, you still have to haul it. You’ve got to dry it and shrink it, and you have to account for phosphorous (P) and potassium (K) removal.” Despite those extra costs, Stute observed that, over 14 site years of data, a positive yield response was present 71% of the time.

“On average, our corn yield response was 2.1%, and soybeans were a little better at 2.3%,” he says. “Average is great, but what I’m really interested in is the variability. Soybean is much less variable than corn.”

Stute plans to continue studying the ways in which cover crops can impact yield, particularly within the first year of planting them. “We’re also looking at the cumulative effects,” he says. “We’re still trying to identify the best management practices to maximize yield, and on the flip side, to look at practices to avoid so you don’t reduce yield. We’re going to generate a lot of data analysis. “But can cover crops pay? Very much.”

"Can cover crops pay? Very much..."

Fighting Herbicide-Resistant Weeds

The practice of planting green — seeding a cash crop into a growing cover crop, rather than terminating the cover crop first — has proven benefits for farmers who use it, says Stute.

“Can planting green suppress our troublesome glyphosate-tolerant or resistant weeds in no-till soybeans?” Stute says. “This research is a work in progress.”

The research he’s doing is important because of the increasing number of weed populations in southeastern Wisconsin that demonstrate resistance to glyphosate and other herbicides. He is particularly concerned with giant ragweed and marestail.

“We don’t have Palmer amaranth yet,” Stute says. “It’s on the horizon. We’ve got it just across the Illinois border and in southern Iowa. That’s another thing to watch and be careful of because the experience in the southern U.S. is something we don’t want to deal with. But it’s on its way.”

His research project, funded by SARE, analyzes 3 trials. The no control treatment begins with a complete burndown, including glyphosate and a growth regulator herbicide to control weeds that are glyphosate-resistant.

“We used LV6 in 2021, but in 2022 because of our shorter planting window we used Enlist,” he says.

The 2 remaining groups have different rye treatments, Stute says.

“We have 40 and 80 pounds to get at the seeding rate difference, and we use the same herbicide,” he says.

The primary question Stute and his research team have been trying to answer is whether planting green will suppress the growth of those resistant weeds, and he’s found that it does.

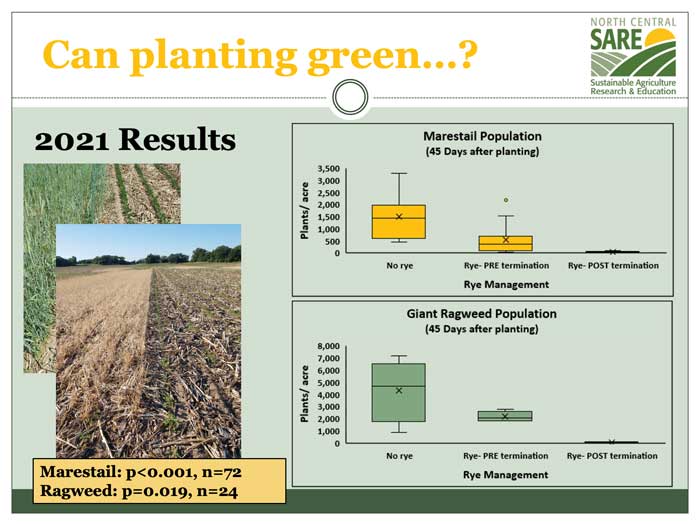

“It suppresses both marestail and giant ragweed,” Stute says. “This is measured 45 days after planting. In marestail, there’s 98% suppression. In giant ragweed, it’s 99% suppression. So yes, it does work.”

Although there was some success in the early termination system, suppression numbers weren’t as high, Stute says. In the case of marestail, there was 64% suppression. For giant ragweed, it was 50%.

WEED CONTROL. Jim Stute’s study shows that planting green resulted in a 98% suppression of marestail and 99% suppression of giant ragweed.

Finding a Middle Ground

While Stute is pleased with the demonstrated weed suppression he’s observed, he’s concerned about a less positive outcome that can accompany planting green.

“By planting green and terminating late, we suppressed soybean yield by 29% in a drought year,” Stute says. “That’s unacceptable.”

With his continued research work, Stute is hoping to find a middle ground, in which a significant number of glyphosate-resistant weeds are suppressed but there’s no decrease in yield outcomes.

“Somewhere between the two is the sweet spot where we’re not impacting yield, but we’re getting the weed suppression,” he says. “That’s what I’m looking for.” Stute is particularly enthusiastic about this research project because of his belief in the importance of resistance management.

“It behooves all of us to practice resistance management because we’ve got nothing new coming down the pipeline as far as new products to deal with resistant weeds,” he says. “We’ve lost glyphosate in a lot of weeds, and that’s unfortunate.

“We are seeing demonstrated weed suppression when we plant green, so we must find that sweet spot that’s somewhere between yield reduction, but we still get the suppression. I’m going to be working hard on that in the future, so we can have our cake and eat it, too.”