“Does it make sense to fertilize soil that will not be supporting a crop?” Chris Perkins doesn’t think so, but his approach to nutrient management may leave a lot of crop consultants and university folks shaking their heads in dismay. Still, the pioneering strip-tiller is producing 300 bushels of corn per acre with just over a half pound of applied nitrogen per bushel yield goal.

The long-time proponent of banded fertilizer placement and owner of Banded Ag, a research, consulting and custom application business in Otwell, Ind., introduced his “feed the plant, not the soil approach” in the highest-rated session at the 2022 National Strip-Tillage Conference. Perkins sees conventional field-wide fertilizer application as wasteful. He urges corn growers to focus on the actual amount of nitrogen required to produce a bushel of corn and apply it where it will do the most good.

“I don’t care about what traditional soil sampling says about fertility in zones or grids,” he says. “I’m interested in what nutrients are needed in the soil actively engaging the roots of the crop. It makes little difference how much nitrogen (N), phosphorous (P) and potassium (K) is in the middle between rows. What pays my bills are the nutrients that actually feed my crop.”

Perkins’s business associate, Chris Kasten, data analyst for TEVA Corp., which sells liquid fertilizer and bio-stimulant products, explains it this way:

“Banding nutrients is like filling a gas can. If you insert the nozzle in the can’s filler neck and pump 2 gallons of fuel, you can be very confident the 2 gallons of fuel you pumped will have been transferred into the can.

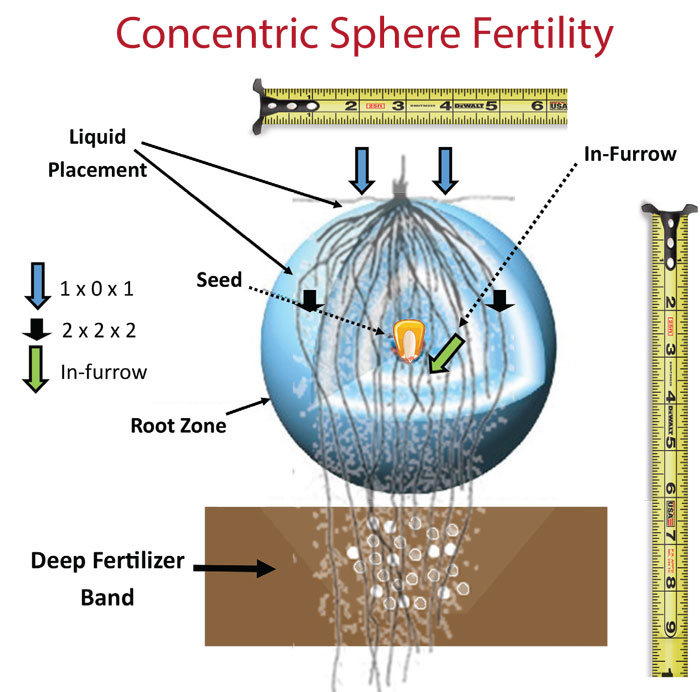

IN THE ZONE. Perkins seeks to place nutrients throughout the globular zone of the rhizosphere to ensure his corn crop has easy access to nutrients from germination through harvest. Photo: Chris Perkins/Banded Ag, LLC

“If, on the other hand, you stand back 10 feet from the can and spray the fuel at the filler opening, you may ultimately get 2 gallons in the can, but you’ll have pumped a lot more expensive fuel and made quite a mess in the process.”

Perkins says the “land between the rows” is still important. The “idled middles” in his fields are still active biologically and responding to manure applications as a source of nutrients for soil microbes and overall soil health.

“There is a lot going on in that part of the field from biology to water movement to nutrient cycling,” he says.

Both Perkins and Kasten agree overall soil health is important, but their goal is to grow a profitable crop in the soil, not change the fertility makeup of the soil itself.

“Soil wants to have a natural balance, and we don’t want to get in the way of that balance,” Perkins says.

Cost-efficient yields come from surrounding his seed with nutrients for the season-long race to harvest, according to Perkins. Farming on 30-inch rows, his continuous corn operation alternates 15 inches either direction each year, so even-year corn rows will be idle in odd years, but they’ll go back in production the following even year.

Residue is Key

Perkins takes it even further than the precise band of nutrients he places in strips below his planter track. He says growers need to consider crop residue and even more precision nutrient management as they seek to boost yields. “High yielding systems create higher yielding systems,” he notes.

The sometimes-outspoken Perkins says when critics of his corn-on-corn nutrient management claim he is “mining the soil,” producing nearly 60% more corn per acre than the annual U.S. average with only .57 pounds of actual applied N per bushel, he suggests they are forgetting his residue management. Kasten details the nutrients that the residue provides.

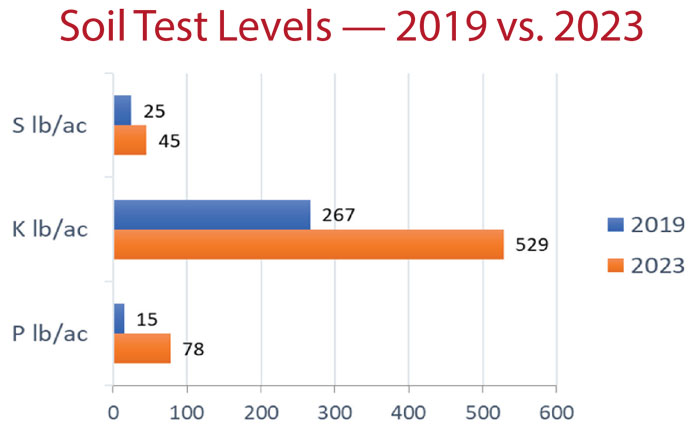

FERTILITY SPIKE. Soil tests from 2019 and 2023 show rise in sulfur, potassium and phosphorus levels in corn-on-corn fields managed by Perkins using Concentric Sphere Fertility concepts. Source: Banded Ag, LLC

“A 300-bushel corn crop produces residue that’s good for about 135 pounds of N, which is the equivalent of 293 pounds of urea; 48 pounds of P205 phosphate or 92 pounds of monoammonium phosphate; 330 pounds of K20 or 550 pounds of potassium chloride; and 21 pounds of sulfur, equivalent to 87.5 pounds of ammonium sulphate,” Kasten says. “That far exceeds most growers’ entire fertility program for their corn crop, and that’s just in the residue of what we’re growing.”

“I guess I am mining what’s in the ground,” Perkins says, “but through residue management and feeding the plant where its roots are interacting with nutrients and microbes (rhizosphere), we’re bringing the nutrients to the top through the corn plant and recycling it back into the nutrient-rich field at harvest. In fact, by doing this we’re boosting our soil test levels. So am I mining or just changing the location of my soil nutrients?”

Perkins and Kasten also say the amount of fertilizer applied precisely into the rhizosphere for the 300-bushel corn yields totals far less than if the entire field was fertilized in traditional nutrient management practices.

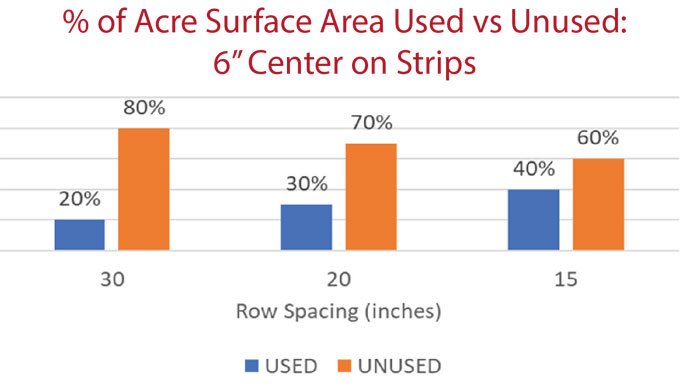

Kasten says the amount of soil actually supporting the crop on 30-inch rows of precisely applied and banded nutrients amounts to about 20% of the total area of the field, so additional nutrients are only being added in close proximity to the plant and represent a fraction of the expense they might if applied on a field or zone basis.

PRECISION PLACEMENT. Using in-row precision nutrition placement, fertilizer applications can be targeted to a much smaller portion of the field than traditional field-wide or zone applications, so total amounts of fertilizer can be reduced to produce the crop. Source: Banded Ag, LLC

Perkins typically pulls annual pre-plant in-row soil samples and has them analyzed using saturated-paste tests, rather than traditional acid-based soil sample analysis.

“Plants take up nutrients in water-based solutions, so we think testing for nutrient availability using water-based solvents only makes sense,” Perkins says.

Rhizosphere Relay

Perkins says his years of observation on banded fertilizer and corn production have convinced him to view plant uptake of nutrients throughout the season as a relay race, rather than as an early-season farming chore.

“A track coach will usually put the fastest runner on the fourth-leg of a four-runner relay to take advantage of the explosive speed that runner can provide after the other three racers have established and held the position,” Perkins says.

“I think it’s the same with corn production. A lot of folks put down pre-plant fertilizer and plant with a starter solution and see a very good stand emergence. Most go on to side-dress as the corn plant matures vegetatively. But we’ve found corn needs nutrients available when it enters and progresses through the reproductive stage too — the point in the crop’s life when it is making the weight that leads to profitable production.”

Kasten says corn accumulates nearly ¾ of its total vegetative weight before it ever produces what the farmer sells.

“Not providing sufficient plant nutrients throughout the growing season is like having the fastest car on the track and allowing it to run out of gas before the race is over,” Kasten says. “A lot of folks ignore this part of the season and don’t produce as much corn as they could if they had used additional, well-placed fertilizer.”

“I don’t care about what traditional soil sampling says about fertility in zones or grids. What pays my bills are the nutrients that actually feed my crop…”

Considering this, Perkins envisions what he calls the rhizosphere relay, a concept that imagines a sphere of soil beneath the corn plant in which the roots operate from emergence through senescense after harvest.

“I call it Concentric Sphere Fertility and use it to make nutrients available throughout the growing season,” Kasten says. “It places nutrients in strategic position to leverage root growth and the natural downward migration of nutrients in the soil over time.”

Perkins says using the spherical approach to fertilizer placement around the seed’s emerging roots mimics the track-and-field relay metaphor.

“When we band fertilizer pre-plant with the strip-till rig, we’re placing nutrients at the bottom of the sphere 7-8 inches deep,” Perkins says. “The in-furrow application at planting puts nutrients close to the emerging radicle and new roots of the seed at germination. At planting, a 2x2 application leaves nutrients on both sides of the seed in the sphere below ground. If we put tubes on the back of the planter and spit fertilizer out the back of them, we fertilize the very top of the sphere. So as nutrients move down, they are always in contact with where the roots are going, and we hit each one of those relay handoffs throughout the season.”

FINISH THE RACE. The kernels on the bottom row are heavier than the top, illustrating why Perkins believes kernel counts are overrated. “Don’t get me wrong, they are important, but not having the program in place to finish what you have produced is more of a handicap than lower kernel counts,” he says. Photo: Chris Perkins

Perkins says Concentric Sphere Fertility places nutrients to the majority of soil volume in the feeding zone of the corn plant.

“It is imperative to concentrate on the rhizosphere for the feeding mechanics of plant nutrition,” Perkins says. “This sphere fertility concept takes that into 100% account for each relay leg of this race.

“The in-furrow is right there at the seed. That’s your first runner in the relay. Then you’re going to enter the percolation zone from the dribbled-on nutrients on the back of the planter, followed quickly by the 2x2 application. By the time the plant begins to enter the reproductive stage, the deep-banded pre-plant has already come into play to finish out the race.”

Win the Nutrient Management Relay Race

Otwell, Ind., strip-tiller Chris Perkins took the stage at the 2022 National Strip-Tillage Conference to explain the benefits of hybrid selection on banded fertility and other significant benefits of strip-till he discovered as he expanded his banded fertilizer system across more than 10,000 acres. “We saw up to more than 50 bushel-per-acre yield increases with the banded fertilizer on some hybrids and no difference on others,” he says. “The results correlated almost to a T on our root observations, so I was convinced there is a difference in the way hybrids respond to banded fertilizer.” Perkins quickly became the highest-rated speaker at the conference, and Strip-Till Farmer Invited Perkins back to give an encore general session presentation at the 2023 conference, set for Aug. 3-4 in Bloomington-Normal, Ill. See insert for details about registering for his highly requested follow up session. Don’t miss your chance to ask Perkins your questions about strip-till!

Chris Perkins, Otwell, Ind.

.webp?height=667&t=1681826451)