Galva, Ill., strip-tiller Brian Corkill began using cover crops on his 1,200-acre corn and soybean operation to help minimize compaction and control erosion in 2012. It wasn’t until Corkill watched a presentation by soil health expert Jim Hoorman that he truly understood the kind of impact cover crops could have on his strip-till system.

“A light bulb went off in my head during that presentation,” Corkill recalls. “I realized there were so many more potential benefits I could get from planting cover crops.”

For Corkill, those added benefits include nutrient sequestration, weed suppression and a positive impact on microbial soil health. He acknowledges that cover cropping is a long term, system-wide project, and demands a bit of patience, but ultimately pays off in the end.

“Some guys tell me, ‘Cover crops are just an extra expense I don’t want to have,’” Corkill says. “I’ve always viewed cover crops as an investment in my soil. It might take up to 5 years to see a return on investment. But I’ve been able to back off more on fertilizer since I’ve started using cover crops.”

Cover Crop Experimentation

Corkill initially planted his fall cover crops with a seed drill, but the process was too time consuming, and he switched to broadcasting with an air seeder. He tries to get his cover crops in the ground right after harvest before making strips in the fall with his 16-row Kuhn Krause Gladiator. After 2023 harvest, he seeded 50 pounds per acre of triticale ahead of corn and 50 pounds of cereal rye ahead of soybeans.

“We’ve run into problems when we seed cover crops only 3-4 days before making strips because we don’t have germination yet,” Corkill says. “The strip-till bar would mix the seed into the strip, and then in the spring, it grows in the strip, which can cause issues for corn.”

He also applied fall cover crops aerially in 2023 — 1 pound of phacelia, 5.5 pounds of buckwheat, 13.5 pounds of winter oats, 12.75 pounds of spring oats and 25 pounds of cereal rye ahead of soybeans. 3 pounds of hairy vetch, 7.25 pounds of buckwheat, 3 pounds of annual ryegrass and 20 pounds of triticale were applied aerially ahead of corn.

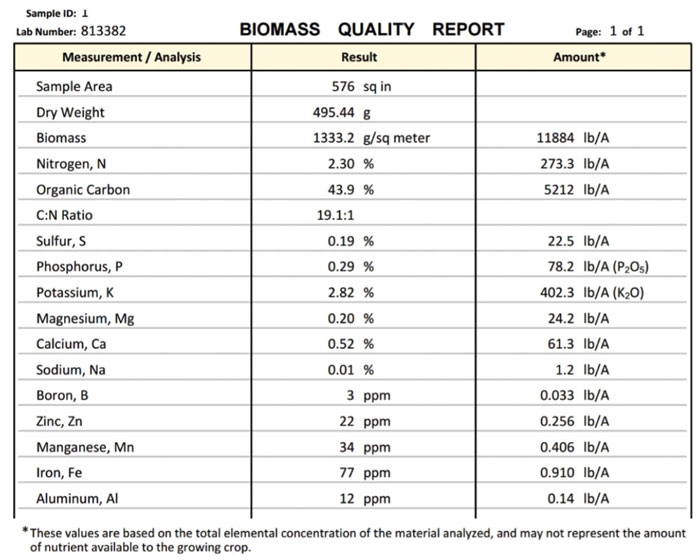

NUTRIENT BREAKDOWN. This biomass report measures the amount of nutrients being sequestered by cereal rye and winter barley on one of Corkill’s fields. Source: Brian Corkill

Corkill plants corn and soybeans green into the cover crop mixes. In his region, soybeans tend to get planted in early April, with corn usually a month after that. The soybeans present less of a problem with cover crop competition and can grow up to a month or so before termination, Corkill says.

“I like planting soybeans green because when it’s wet, that cover crop is taking moisture out of the soil,” Corkill says. “When I plant into it, I’m planting into a decent seedbed.”

Corn is a little more demanding; cereal rye can grow prolifically in the spring, and if not promptly terminated, shade out young corn, he says.

“I’ve been able to back off more on fertilizer since I started using cover crops…”

“Cereal rye is not hard to terminate, but you really have to stay on top of it because once it gets the right weather, it can really take off in a short period of time and cause some issues with corn,” Corkill says.

Timely management can take care of those issues, Corkill says. He chemically terminates his cover crop with Roundup up to a month after soybean planting and as soon as possible for corn. He wants to try a roller crimper on his cover crop, but no one in his region seems to currently use the method, and local dealers are reluctant to bring in an attachment to test out. Until one becomes available, prompt herbicide application acts as a good way to terminate the cover crops.

Corkill has also tried interseeding, though the results were mixed. He tried topdressing knee-high corn with 18 pounds of annual ryegrass, 4 pounds of clovers and 1.3 pounds of radish. He achieved great radish growth and good ryegrass growth. Clover establishment was spottier, he says, as harvest residue and resulting tillage adversely impacted the cover crop.

Corkill says the experimentation, however, is important because with cover cropping, as with most every other aspect of strip-till, the ability to learn and adapt is vital. For example, when cereal rye grew too fast for young corn, Corkill switched to other mixes including triticale and winter barley.

“Those species don’t grow as aggressively as cereal rye early in the spring and they were easier to manage,” Corkill says.

Feeding the Soil

Cover crops have done a good job of suppressing Corkill’s most problematic weed, waterhemp, and reducing his number of herbicide applications. While weed control has been a huge benefit, Corkill perhaps gets the most bang for his buck from the amount of nutrients cover crops provide to the soil.

Corkill began biomass sampling his cover crops in 2017 to determine what nutrients were being sequestered. He also soil tests every 3 years and conducts block trials on different fields. He currently employs an independent consultant to manage the data and make recommendations.

“I’ve always viewed cover crops as an investment in my soil…”

Initially, after post-harvest crop testing, Corkill had aimed to replace 100% of nutrients lost in removal; now, testing and management have gotten that down to about 65%, with cover crop sequestration making up for the residual difference. From both a fiscal and stewardship standpoint, that’s a win for Corkill.

“One test we did looked at cereal rye that was 6-foot tall and some winter barley on ground that I had put anhydrous on in the fall,” Corkill says. “The test shows that the cover crops sequestered about 275 pounds of N per acre. That field only had 100 pounds of N applied in the fall, so the cover crop was also sequestering any mineralized N that was available. If you keep growing cover crops every year, then you’re going to have more mineralized N than you might normally have if you weren’t growing a cover crop.”

While he can’t put an exact number on fertilizer savings since he started using cover crops, Corkill estimates he saved about $20 per acre on P and K, and $25 per acre on N in 2023.

“After I first started using cover crops, I was applying about 75% replacement rate for P and K, and now I’m applying 55%,” Corkill says. “Some of the P and K savings could be attributed to placement as well with the strip-till bar.”

Nutrient Management Strategies

Brian Corkill’s family has been farming with a conservation-first mindset since 1983 when they started no-tilling. He began strip-tilling in the late 1990s shortly before adding cover crops to his system. Always looking for ways to improve, Corkill has tweaked his nutrient management considerably over the years.

Corkill initially sprayed anhydrous as his primary nitrogen (N) application, but as he became more familiar with strip-till, he gradually began using dry fertilizer. He started the slow switch in the mid-2000s and has now stopped using anhydrous all together. Likewise, initial broadcasting of fertilizer gave way to strip fertilization, which has proven more effective, Corkill says.

In addition to moving away from anhydrous, he has also backed away from phosphorous (P) and potassium (K) applications as much as possible. Using a Montag GEN II twin bin fertilizer system, Corkill variable rate applies dry fertilizer in the fall — MESZ, which includes MAP, sulfur and zinc, along with some K. Corkill also uses an in-furrow starter fertilizer with his 24-row John Deere planter that includes 4 gallons of 10-34-0 and zinc, but he’s thinking about making some changes in 2024.

“I think I’m going to go away from my starter mix and focus more on applying N with my planter,” Corkill says. “I’d like to make sure the N is applied right where the corn plants are, so there’s better uptake early in the season.”

Using his high-clearance sprayer, Corkill makes multiple sidedress applications of N, K and sulfur at variable rates as late as V12-V16. The ability to target the root system through sidedress applications, while simultaneously being less reliant on rain, has proven beneficial, and allows him to make “spur of the moment” applications. That flexibility means that fertilizer applications can truly be specific and varied based on the needs of an individual field, Corkill says.